Fieldwork

Mercifully, 2002 saw no repetition of the Foot and Mouth epidemic which cut such a swath through British agriculture and our own 2001 field program. We had expected to carry out two excavations, although in the event only the larger was able to take place. We also conducted another of our very large, whole Roman fort, geophysical surveys and continued our air photographic program. As ever, our work has attracted volunteers from a wide geographical area, with diggers from Ireland, Germany, Australia and Canada taking part this year, alongside those from the UK.

East Coldoch

For many years, archaeologists have complained that not enough has been done to study the impact of the Roman incursions on the indigenous population of Scotland. This has been to no small degree the result of the way in which Roman and Iron Age archaeology have been studied in the past, with Romanists and prehistorians forming very separate groupings, who have traditionally shown remarkably little interest in each other’s work. Worse still, much of the attention of the Iron Age specialists in recent decades has been directed towards the so called “Atlantic” cultures of the islands and western seaboard and, although this now appears to be changing to some degree, more easterly regions, such as the Gask area, have been neglected to the extent that a recent research agenda described the Iron Age of Stirlingshire as a knowledge “Black hole”, with the situation in Perthshire only a little better. This statement contains an element of hyperbole, for there has been good work in the area, not least by Lorna Main and Ewan McKie. Nevertheless, the fact that it could be made at all is an indication that much remains to be done.

The Gask Project, although primarily a Romanist organisation, is interested in studying native sites occupied during the Roman period, to try to determine something of their interactions with the occupying power and to measure Rome’s likely impact on the prevailing political, social and physical environment. In particular, it was hoped that the supply needs of the 12-18,000 strong Roman army of occupation might have caused changes to native agriculture which might leave archaeological traces, especially given the growing evidence for a longer than expected Roman presence. There was, however, one major problem in selecting suitable sites for study; for although large numbers of Iron Age sites are known in the area (mainly from Air photography), these are notoriously difficult to date with any precision without excavation. The Project has thus been attracted to sites where air photographs have revealed multiple structural periods. These suggest a lengthy occupation and thus provide a statistically higher chance of Roman period usage, but they also have the added advantage of offering insights into long stretches of Iron Age history on a single site. This means that any Roman period occupation can be set into a longer term context, which should make any changes easier to detect, but it also allows data on lengthy time periods to be collected in a relatively economical manner.

Excavations at the first such site, East Coldoch, began in earnest in 2000 (after a test trench in 1996) and the delayed third season took place in August 2002. The site lies a few miles to the

of the Roman fort of Doune and a few hundred meters east of Coldoch Broch. From the air it showed a total of four superimposed structures: two palisaded enclosures, a small round barrow, and a defended homestead with a heavy penannular ditch. All of these sites overlapped, which meant that no two of them could have been in use simultaneously, and a lengthy occupation seemed assured. The 2000 season established the order in which the main structures were built and also revealed that archaeological deposits had survived in a remarkably good state of preservation, especially for a crop mark site. This allowed the excavation to yield more detailed data than we had dared hope, but it also lead to slower work rates and the 2002 season was intended as a relatively straightforward catch up exercise. Instead, the site deluged us with yet more new surprises and the greater complexity that has resulted means that yet another season will be needed next summer. The quality of data being obtained make this thoroughly worthwhile, however, and we look forward to the 2003 season with growing curiosity. Something of the complexity involved can be seen in the compulsory Data Structure Report prepared after each season for Historic Scotland. This is just a list of the information recorded, but it now runs to 87 closely typed pages and records, i.a., almost 450 contexts, 91 site drawings and close to 2,000 photographs.

Amongst the highlights from the 2002 season were the discovery of what seems to be yet a third palisaded enclosure (not visible from the air), along with an inter-cutting series of curved grove features which probably represent internal palisaded enclosure houses. The most exciting results came from the defended homestead, however, which was already known to be the latest structure on the site. The 2000 season had hinted that the large (12m diameter) roundhouse might have at least two structural periods, both of which eventually burned down. This year’s excavation confirmed this and greatly clarified our understanding of the structures involved. The discovery of load bearing postholes inside the house, but well away from its centre, might suggest that at least one of the phases had an upper floor and this might be supported by the fact that no sign of a hearth has been found at ground level, something normally the focus of any roundhouse. Instead, we may have growing evidence that the ground floor was used for the storage of agricultural produce. Quantities of carbonised grain were found in 2000 as these levels were initially explored, but the trickle became a flood in 2002. Every cubic millimetre of the roundhouse destruction and floor deposits has been either sieved or collected as bulk flotation samples and, although the latter have not yet been processed, we already have kilograms of grain, mostly barley, but with some wheat and oats. It is possible that stock might also have been kept on the ground floor, but although samples were taken for phosphate analysis, we have been advised that the level of burning is such that the material is too contaminated to provide meaningful data.

Grain seems to have been extremely important on the site. This year’s work revealed an unusual, rectangular, posthole structure between the roundhouse door and the ditch entrance. Several similar structures have been found on other Iron Age sites in Scotland. Nicknamed “four posters”, they seem to be connected with (possibly elevated) grain storage and certainly the whole area around the feature appears to be saturated with grain, with over 1,900 barley grains being found in the fill of just one of the postholes. At the same time, quantities of barley chaff were found a few metres further north in the lower fills of the defensive ditch, suggesting that grain may have been threshed and winnowed in this area. Something of a paradox still remains, however. For, despite the prevalence of grain on the site, an analysis of pollen from the ditch silts showed no sign whatever of cereal pollen. Instead, it pointed to a similar open, grazed landscape to that found elsewhere in the area, including the Gask frontier itself. Potentially this means that the grain was not grown on or near the site and so may show that Iron Age societies traded in bulk goods. That said, cereal pollen, although windborne, tends not to travel far and so this apparent absence may only mean that the grain fields were not within a kilometre or two of the site. Further silt samples were taken this season to be searched for the smallest trace quantities of cereal pollen, and the results should allow us to shed more light on the exact position. Another interesting aspect of the possible four-poster is the unusual precision with which it was built. It is an exact rectangle with perfectly right-angled corners and has a length to width ratio of 1:2 to within a few millimetres.

The earlier seasons located two palisade slots inside the roundhouse ditch, which had been interpreted as the revetments for a box rampart. This year’s work put paid to that hypothesis, however, as the slots proved to predate the ditch. There is also now doubt whether the two are contemporary inter-se and it is possible that one represents an earlier defence for the roundhouse whilst the other may be part of the newly discovered third palisaded enclosure.

Perhaps the most important discovery of the 2002 season concerns dating. As already mentioned, we had hoped that at least one of the structures on the site belonged to the Roman period. On purely morphological grounds, the defended roundhouse had seemed the most likely candidate, but until now there had been no proof. This year’s excavation, however, found fragments of late first century Roman square bottles in association with the roundhouse, which provides both dating evidence and an indication that the inhabitants had access to Roman trade goods. One assumes that the bottles were originally obtained for their contents, probably wine or oil, which would have represented luxury goods for the Iron Age population. Nevertheless, the empties would have retained some utilitarian value and may have been kept, or even traded in their own right, so it is probably not safe to draw too many conclusions from the presence of the vessels. What does matter is that the site and its environment can now be tied more firmly to the time of the Roman occupation and its reasonably prosperous state can be seen against that background. At the same time, we also now have evidence that the site survived the occupation, for although it eventually burnt down, C14 evidence shows that this did not happen until the 2nd or 3rd centuries. Moreover, there are no signs of violence associated with the episode, which seems to have been accidental. Certainly the inhabitants seem to have survived, for there is strong evidence that the ashes were raked through, presumably to recover any valuable artefacts, and that the house was then rebuilt.

Occasionally archaeology can spring wonderful surprises and give insights into ephemeral details that one would not expect to leave any trace. One such is the weather. It rapidly became clear that the primary roundhouse had burned down with unusual ferocity. The northern part of its 90mm thick clay floor had overlain a levelling layer of stone slabs, and the fire had been so intense that the scorching had penetrated to the stones themselves. This suggested that the house had burned down during a prolonged dry spell, when the structure was tinder dry. At the same time, the burning grew progressively less intense towards the north-west, so that the clay floor at the north-western edge was all but untouched. It would seem likely, therefore, that the house burned down during a summer heat wave, on a day with a north-westerly wind.

Of course, archaeology also has its frustrations. One of the missions for the 2002 season was to examine the entrance area of the most complete of the palisaded enclosures. This had shown beautifully from the air in photographs taken in the 1980s, but our trench produced no sign. The site was re-surveyed to make absolutely sure that we had dug in the right place and the trench was extended to give a better margin for error, but still there was nothing, and the only remaining conclusion is that continued ploughing has removed every trace. Certainly, the one ploughing conducted between the 2000 and 2002 seasons had caused a noticeable deterioration in those parts of the site examined in both years and the case of the vanishing entrance was a salutary reminder of the gradual erosion of the archaeological record which is continuing year on year all over the country.

Inverquharity Roman fort

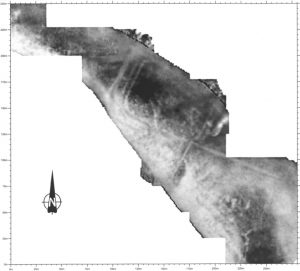

For some years now the Project has been conducting a series of very large geophysical surveys. Where possible both resistivity and magnetometry have been used, but many of the local subsoils have too high an iron content for magnetometry to function well. This is a shame as the two methods produce data on different aspects of a site and it has also forced us to rely on resistivity alone, which is a slower technique to operate. Our ambition had been to survey targets as large as entire Roman forts, but for years we had listened to dire warnings that this was simply unfeasible with resistivity, at least within a reasonable budget and time scale. As reported in last year’s annual report, however, 2001 gave us the opportunity to put this to the test (at Historic Scotland’s expense). The result was a 17 acre survey of the fort of Cardean, which took in the entire fort along with parts of its two annexes and general surroundings. That success has given us the confidence to go further and, over the next few years, we are hoping to survey all of the non built-over Roman forts north of the Forth-Clyde line (except Ardoch, which has been surveyed by the University of Glasgow) for which the land owners’ consent can be obtained (a maximum of ten at present). 2002 saw the first of this series: a survey of the whole of the fort of Inverquharity (Kirriemuir), along with its annexes and part of a small accompanying temporary camp. The site was chosen for a number of reasons. For example, Air photographs had shown signs of native activity outside its defences, which meant that more light could be shed on the native side of the equation. It was also relatively small, which allowed us to experiment with a modified working system which had been developed after the lessons learned at Cardean. This involved the use of three, rather than two, person meter teams and might have proved expensive on a larger site if it didn’t prove effective.

Inverquharity was discovered from the air in 1983, but although it has been photographed several times since, it is totally invisible on the ground. Technically, opinions differ as to whether it should be called a “small fort” or a “fortlet” (we tend to the latter), since the site itself is hardly more than an acre in size. It did, however have two apparent annexes which are collectively more than twice the size of the parent installation. The original plan had been to survey a 5 acre area, but the increase in work rate brought on by the larger meter teams turned out to be larger than anticipated and a 7.5 acre survey was eventually completed in a day less than had originally been planned for the smaller area. This is still much smaller than the Cardean survey, but it was conducted with just one meter, rather than two and in only half the time, despite a certain amount of down time caused by a broken probe. Indeed the three person teams proved to increasing the area surveyed per person day by an appreciable margin and our future work will be able to take place on a more cost effective basis.

The results more than justified the work involved. The fort had shown fairly well from the air, but its entire northern side lies under tree cover and had never previously been seen. This was a particular problem since the plateau on which it stands shows obvious signs of erosion and although it seemed certain that some of the fort had been lost, there was no way of telling how much. The geophysical results produced a perfect image of the defences and showed that the ditch curves for both of the northern corners had partly survived, so that erosion has caused less damage than we had feared and probably none at all to the site’s interior. Elsewhere, the defences perfectly match plans drawn from rectified air photographs, thus confirming their accuracy. The annexes, on the other hand, were shown to cut the fort’s ditches, making them less than fully contemporary. They may, of course, be the result of a later modification, but they also proved to have rather non-Roman looking angular corners and it now seems more than possible that they do not relate to the fort at all. Elsewhere, the temporary camp also seemed likely to have suffered erosion at its northern end but, again, the survey was able to pick up part of its north-western corner curve (the north-eastern side was not surveyed), showing that the damage was minimal.

Perhaps the most exciting find, however, concerned the native structures. Air photography had already revealed five ring features and a souterrain in the fort’s immediate vicinity, but the geophysics added at least four more roundhouses and probably more. This combines to suggest the presence of a significant settlement around the fort, a picture similar to that revealed at Cardean. Most of the structures lie clear of the fort and it is tempting wonder whether they might have grown up around it, but what makes the discovery particularly interesting is that one of the roundhouses is so close to the souterrain that they appear to be physically linked. It has long been thought that at least some souterrains might be attached to roundhouses, but in practice, the phenomenon has rarely been seen. This is partly because the underground souterrains tend to survive in places where more superficial features have been ploughed away, and partly because the stone linings which characterise most known souterrains were much easier to see than timber roundhouses during the early days of archaeology. It has to be admitted, though, that even today souterrains tend to be seen as more interesting than roundhouses and so for reasons of cost and/or excavator interest, a souterrain’s immediate surroundings are still often virtually ignored. The geophysical evidence from Inverquharity is unequivocal, however, and the result should act as a spur towards using this economical technique at other souterrain sites, whether or not excavation is planned.

Raith

As already mentioned, the Project had intended to run a second excavation this year. The original plan was to carry out trenching to address a number of problems concerning the temporary camps around the “Glen blocker” fort of Bochastle, along with a whole site geophysical survey of the fort itself. But in the spring of 2002 we received an offer to run a BBC funded excavation at the Gask tower of Raith. This site has long been on the Project’s wish list as it has the potential to shed additional light on the development and life span of the whole Gask Frontier, so we were very happy to accept and, as considerable work was involved in mounting the excavation, including an SMC application, the Bochastle work was shelved for a future season. The site was roughly excavated during the construction of a water tank in 1901 and produced the remains of a normal Gask tower. Its real importance, however, lies in the fact that an air photograph has shown what appears to be a fortlet ditch surrounding the tower. We already have a similar configuration a few miles to the east at Midgate, where a Gask tower and fortlet sit side by side, only 13m apart. There was obviously no need for two installations so close together and so the two cannot be contemporary. Unfortunately, they were just far enough apart that their ditch upcast did not overlap, which means that it has not been possible to determine which came first, or what time scale was involved. This data should be more available at Raith, however, since the tower there is wholly inside the possible fortlet. We had already carried out a geophysical survey of the site and the farmer had seemed happy to allow excavation, so work went ahead to recruit a dig team and obtain Historic Scotland’s blessing. Unfortunately, the farm had changed hands since our survey was conducted and although the new owner seemed interested in the work, he became adamant in asking several thousand pounds for access to the land. The BBC were prepared to offer a lower, if still substantial sum, but negotiations got nowhere and the excavation eventually had to be abandoned.

This is a great shame and, unless the farmer eventually changes his mind, a solution to the issues at stake here might have to wait a generation. In the meantime, the field is usually in cereals, which will inevitably subject the archaeological deposits to further plough damage and, if it is not already too late, it might now take very little to cut any remaining stratigraphy between the two features. Obviously one cannot blame any farmer for trying to grasp a windfall when it is offered, especially in the current very difficult agricultural climate but, in the present instance, it would appear that all concerned lost out for want of a reasonable compromise and he is most unlikely to get another such offer. All we can say is that this has been a unique experience on the Gask. We have long been overwhelmed by the welcome and kindness shown to us by hard pressed farmers in the area, despite the fact that, in normal circumstances, the Project can never pay anything for access. We can only offer farmers an insight into the history of their land and are grateful that to most this seems to be enough.

The incident may have been somewhat frustrating., but not all of our work was wasted. We were able to take the time to fully peruse and rectify the air photographic data for the site and prepare a composite plan, onto which we have also mapped our geophysical data and this will be published in due course, probably in combination with the Inverquharity report.

Air Photography

The wet spring and summer made 2002 a disappointing crop mark year, with even trusty perennials failing to show. As a consequence, we spent only a few hours airborne and have conserved the Project’s flying budget in the hope of obtaining good shadow or soil mark conditions over the winter. Nevertheless, there were a few curious exceptions to the general gloom and, for reasons we do not really understand, some prehistoric structures showed well even on sites where known Roman sites remained invisible. As a result, a number of new features were discovered, most of which seem likely to be roundhouses. Perhaps the most important discovery is a possible new souterrain inside the Roman fortress of Carpow. One such feature is already known to have been cut by the site’s defences, but the new one is in the interior. Interestingly, a recent report had pointed to the discovery of native artefacts in the fortress and suggested that they might provide evidence for trade with the natives. But, if the fortress simply took over the site of a souterrain settlement, the new Air evidence would imply that the native material was residual.

In addition to our own flying, local flying instructor Sandy Torrance has been kind enough to send us several sets of air photographs taken during his own flights. These have included a superb series of images of the Roman fort of Strageath showing as a soil mark, and an impressive series showing East Coldoch under excavation. Mr Torrance has also been kind enough to provide pictures of the local rivers in flood, an all too common sight of late. This continues work begun by ourselves last year in the Isla valley, which attempts to correlate flood patterns with the distribution of prehistoric settlement. The evidence to date has proved fascinating. The 20th century may have been foolish enough to build in flood plains, but the Iron Age was not, although they often went very close to the high water marks.

As in previous years, our own flights were made from Scone airfield, and we are again extremely grateful to Bill Fuller for volunteering his services as pilot. Mr Fuller’s expertise and professionalism always allows the maximum value to be gained from each hour of flying time and we were further assisted this year by the acquisition of a moving map GPS machine. The latter now has the location of every known Roman site in north-eastern Scotland programed into its display, along with many of the more important native sites and it has made precision navigation and the later identification of individual photographs very much easier than before.

Unlike this year, 2001 was an excellent flying season which saw the Project taking close to 1,000 air photographs. These have now been digitised and fully indexed, and a double CD-R set has been produced and distributed to a number of interested bodies, including the NMRS and the Perthshire SMR. As well as being of immense value to our own research, lectures and publications, our air photographs are increasingly being used by others. For example, the University of Glasgow has made use of last year’s discovery of a new cursus monument for a study of such sites, whilst the newly published excavation report on Shanzie Souterrain (near Airlie) contains air photographs provided by us.

Desk Assessments and Collaborations

The Gask Project has again been able to work with a number of specialists and other workers to gain additional information from both our own expeditions and those of others.

Roman Roads

The Project has continued to co-operate with Roman road hunters Dr T.M. Allan (Aberdeen) and Dr D. Simpson (Stirling). As in previous years, their advice was of great help in planning some of the details of our Air observations and they will hopefully be able to conduct follow up surface work armed with digitised versions of our photographs. The Gask Project would like to take this opportunity to salute the life’s work of Dr Allan, now in his 80s. He is well known in the field and the author of a book on Roman roads and had remained a very active field worker at an age when most might have taken life more easily. Sadly, his future activities may be somewhat curtailed, as he has felt compelled to give up driving, following a minor road accident, but we should still be seeing activity from him from time to time in concert with others. Dr Woolliscroft had a trip out with him this spring to examine possible signs of a road between Cargill and Cardean forts. During the course of the survey fragments of glass were picked up immediately north of Coupar Angus, which have now been identified as late first century Roman.

Fieldwalking

Gamekeeper, Mr B. McIntosh, has continued to send us ceramic material picked up on the fields around the eastern end of the Gask Ridge. Last year we reported on the find of a single sherd of possible late third or early fourth century Roman pottery from a spot near the Gask tower of Peel. This appears to show that Roman material was still reaching the area in a period during which there was no known Roman military activity, and presumably points to a native settlement in the vicinity that still had access to such goods. Interestingly, our own geophysical survey of the tower in 1999 showed what appeared to be a native site attached to the tower and possibly reusing its defences. We cannot be certain as yet that this is the source of the late Roman finds, but we are monitoring the situation with interest. The original pottery analysis was conducted by Dr Alex Croom (Tyne and Wear Museums). At her request, we submitted the pottery this year to Dr Alan Vince for a second opinion, along with two more sherds submitted more recently by Mr McIntosh. Dr Vince has now confirmed Dr Croom’s identification and assigned similar dates to the new sherds, making the original story more definite and we are considering further excavations at Peel at some point. Mr McIntosh has also now sent pottery picked up from the temporary camp of Forteviot and this too has been dispatched for analysis.

In addition to this material, Mr A. Dick has very kindly allowed access to his own field walking finds from the fort of Cardean, which are being analysed and will be included in Dr Hoffmann’s forthcoming report on the site.

Inverquharity

The geophysical survey of Inverquharity will be prepared for publication early in the new year and it seemed logical that the report should incorporate any other unpublished work. So far as we can tell, the only excavation done on the site was some trenching conducted by J.K. St.Joseph and G.S.Maxwell shortly after the site’s discovery. Sadly St.Joseph died before writing this up, but Mr Maxwell has very kindly agreed to prepare a report for publication alongside our own.

Stormont Loch

Dr Hoffmann is currently co-operating with Dr Fraser Hunter of the National Museum of Scotland to produce a report on a Roman bronze trulla (a field cooking pan) found near Stormont Loch and now in Perth Museum. The pan is a piece of Roman military equipment, but analysis of repairs suggests that it later came into native hands. The pan has generally been assumed to have been thrown into the loch as a votive offering at the end of its life, but it was actually found on dry land. The loch has, however, contracted substantially over the last two centuries thanks to drainage and agricultural improvement works and, in addition to study of the piece itself, a great deal of archive work has been done to establish the loch’s original size. The results to date would suggest that the piece was never in the loch and may be a normal archaeological loss.

Archive Work

Since its foundation, the Project has been involved in tracing and publishing earlier work whose original instigators were, for whatever reason, unable to publish their results themselves. This has continued in 2002 and Dr Hoffmann has spent the year on sabbatical, writing up Prof A.S. Robertson’s large scale excavations at the fort of Cardean in the 1960s and 70s. Her book length report is now well advanced and should be ready for publication at some point in the spring of 2003.

Our attempts to look further into Roman/native interactions over the past few years have started to produce at least hints of a greater than expected level of co-operation between the two. At the same time our whole fort geophysical surveys have revealed native settlements around the forts of Cardean and Inverquharity. We have now scanned our own and other air photo archives for signs of such settlements around other Roman sites in Scotland and find parallels around Cargill and the rather odd camp of Dun on the Montrose basin, which may actually represent some form of fortified landing facility. There is even a tendency for Roman temporary camps to be sited close to native communities. As yet, we have little idea of the relative dates of these features and there is thus no guarantee that any, let alone all, were contemporary with the Roman occupation. Nevertheless, a number of potential scenarios spring to mind and further work is undoubtedly needed. For example, these sites tend to occupy good defensive and settlement positions, often on firm, well drained land close to water sources, and it may well be that the Romans simply picked them for the same reason the natives had, possibly displacing their local inhabitants in the process. Secondly, it might be that the Roman’s were deliberately positioning themselves on local power centres, to either monitor, or even support, local leaders. A final possibility is that the Roman sites welcomed the continuation of native settlement, or even attracted it, to act in the manner of proto fort vici. It has been noted that very few of the Roman forts of Scotland (in any period) have traditional Romanised civilian settlements outside their walls, although they seem to have been encouraged elsewhere. But it may be that we have been looking for the wrong thing and that locals, or even non-locals using local architectural techniques, were able to step into the gap.

Finally, our continued work with air photo archives has produced a few indications that the Romans may have sought to actively avoid impinging on native ritual and funerary sites. One example is Raith, where our studies have revealed a series of what appear to be cist burials immediately outside the Roman site. Raith happens to have the best potential vantage point of any of the Gask towers and yet it was built about 40m to the east of the best possible position, conceivably to avoid one of these features. Other examples include the ditch of one of the Ardoch temporary camps, which passes through an area of marshy ground, apparently to avoid cutting another cist group. This is consistent with Rome’s often reverential approach to an enemy’s gods and other sacred entities, which could include the dead. She would often try to recruit them to her own cause rather than defeat them and we may see something of this process at work here. Indeed, elsewhere, for example the Hadrian’s Wall fort of Great Chesters, there are signs that the Roman army may have deliberately adopted established native burial grounds to bury its own dead, even when these lay at some distance. This work is still at a very early stage, but a preliminary report was given to this year’s Air Archaeology Research Group conference. A more detailed version will be prepared for the triennial International Congress of Roman Frontier studies, to be held in Hungary next summer and will be published in the congress proceedings.

Publications and Publicity

2002 has seen the publication of a number of Gask Project reports. In addition to the usual short notes in “Britannia” and “DES”, the reports on our excavations at Cuiltburn and the Gask tower of West Mains of Huntingtower appeared in PSAS. 2002 also saw the launch of the new popular history magazine “History Scotland” and the Project made its presence felt as quickly as possible with an article on our principle results, lavishly illustrated with colour (mostly Air) photographs. In addition, our web master, Peter Green, has continued to do a wonderful job of updating our web site.

The biggest publication event of the year was the appearance of our book “The Roman Frontier on the Gask Ridge“. This was originally submitted in January 2001, but delays at the publisher meant that it still remained unpublished this spring. Reluctantly, the decision was taken to move publisher and, after a certain amount of rewriting to bring it back up to date, the work finally appeared with Archaeopress this summer as part of their “British Archaeological Reports” series. The book consists of two parts. The first is a detailed summary of the Project’s results to date and the light these have shed on the Roman occupations of Scotland. The second contains a series of survey, excavation and other reports which would have made rather short independent papers. These include, i.a., work at six suspected temporary camps, four Roman forts, the Roman Gask road and Peel Gask tower, along with an account of the glass of Roman Scotland and the late Prof J.K. St.Joseph’s excavations at the Gask tower of Shielhill North. Finally, two appendices provide map references for every known Roman site in northern Scotland and detailed morphological data on the Gask installations.

The book seems to have caused something of a media stir in Scotland, by announcing our growing suspicions that the Romans may already have reached as far north as Perthshire before the arrival of the famous governor Agricola. It is not often that an academic monograph hits the headlines, but the Herald and various more local papers had articles and the BBC Scotland radio news rang to conduct an interview. It has to be admitted that we had not appreciated how deeply Agricola seems to have penetrated the Scottish consciousness, for within a deluge of correspondence asking for more information, were one or two letters so deeply shocked that we could even say such a thing that they teetered on the brink of hate mail. One can only hope that this interest will help the book’s sales.

The Coldoch excavation also attracted media interest and articles appeared in a number of papers, including, again, the Herald. There was even an article about our work in, of all places, the staff magazine of HM Land Registry, written by a former dig volunteer.

In addition to the printed word, 2002 saw the making and broadcast of a television program about our work. The program was part of BBC 2’s “Time Flyers” series which was designed to show something of the value of aviation in archaeology and the Gask issue covered the frontier itself, our own flying activity, the East Coldoch excavation and even a (thankfully successful) experiment in frontier signalling. The short, half hour format and the fact that it was designed to be broadcast in the early evening and so needed to be as comprehensible to children as to adults, inevitably resulted in a rather superficial approach, but we were very impressed by the care with which producer Sandy Raffan made sure she had her facts straight and understood our evidence and conclusions. This has not always been our experience with other producers in the past and, as this was the longest we have yet been involved with an individual TV project, it certainly made for a smooth working relationship.

In addition to the printed word, 2002 saw the making and broadcast of a television program about our work. The program was part of BBC 2’s “Time Flyers” series which was designed to show something of the value of aviation in archaeology and the Gask issue covered the frontier itself, our own flying activity, the East Coldoch excavation and even a (thankfully successful) experiment in frontier signalling. The short, half hour format and the fact that it was designed to be broadcast in the early evening and so needed to be as comprehensible to children as to adults, inevitably resulted in a rather superficial approach, but we were very impressed by the care with which producer Sandy Raffan made sure she had her facts straight and understood our evidence and conclusions. This has not always been our experience with other producers in the past and, as this was the longest we have yet been involved with an individual TV project, it certainly made for a smooth working relationship.

Other work has been dispatched for publication during the year. Dr Hoffmann was one of the co-editors of the Proceedings of the 2000 Roman Frontiers Congress (held in Oman) in which both she and Dr Woolliscroft have papers. This has now gone to the printers and should appear early in 2003. She has also prepared a study on the problems of Tacitus’ account of the Roman invasion of Scotland, which is to be published next year by Routledge, and a comparative paper on glass finds from northern military sites, to be published by the Glass Association.

As ever, Project members have continued to give lectures to a variety of academic, student and amateur bodies and a number of local societies visited the Coldoch excavation. Dr Woolliscroft gave talks to the Friends of Innerpeffray Library and the Stirling and Liverpool Archaeological Societies, whilst Dr Hoffmann gave our annual talk for the Perth “Doors Open” day, a two day school on Roman Scotland for the University of Manchester, and a lecture to the Bangor University Classics Society. In addition, both Directors gave papers to a special session of the Roman Northern Frontier Seminar, held in Newcastle in response to our own and others’ evidence for an earlier and longer 1st century occupation of Scotland. The session was interesting not least for the relatively low level of resistance to the ideas we have been offering. Only a few years ago, they would have seemed simple heresy (to ourselves as much as anyone), but our own work and reanalyses of finds types such as coins and pottery by others have built up a revised picture which is getting more and more difficult to ignore, however much some will continue to try.

Finally, Dr Woolliscroft’s paper on Roman/native interaction to the AARG conference in Canterbury has already been mentioned, but Dr Hoffmann also gave a paper on her own recent Air discovery of a vanished, but palatial, country house near Kinclaven Castle.

Affiliations

For the last few years the Gask Project has been in the less than ideal situation of having its resources spread between two different Universities in two different countries, with Dr Woolliscroft and the Project itself based in Manchester, and Dr Hoffmann at University College Dublin. The situation was made rather worse by the fact that Dr Hoffmann was based in the Dept of Classics where the needs and value of field archaeology were not always understood, whilst Manchester has been becoming ever more theory centred. The issue has now been solved by an invitation to move the Project to SACOS (School of Archaeology, Classics and Oriental Studies) in the University of Liverpool, with both Directors appointed as Honorary Research Fellows and providing teaching and field training. The move was finalised this autumn and we have been delighted by the enthusiasm with which we were received. Hopefully this will be the start of a long and mutually beneficial relationship.

Sponsorship and Acknowledgements

The Project continues to be sponsored by the Perth & Kinross Heritage Trust, whose support has been both indispensable and deeply appreciated. In 2002, the Trust funded our air photographic flying program, the purchase of additional air photographs and almost all of our specialist reports for sites other than Cardean.

In addition to this long term funding, we must also express our gratitude to Historic Scotland who are funding Dr Hoffmann’s sabbatical, and who have also been kind enough to fund conservation work and a number of specialist reports vital to the completion of the Cardean report. Our long standing corporate sponsor (which continues to insist on anonymity) has again provided material support in the form of a major upgrade to the Director’s desk top computer (itself their property) to bring it up to state of the art specification. They also provided our new GPS machine on their usual long term loan, along with software to allow it to download flight tracks to GIS maps.

The Project continues to owe thanks to Stirling based doctor and amateur archaeologist Dr David Simpson, who again provided medical services during our fieldwork, and to Mark Hall and Fraser Hunter who have been of enormous help in tracking down material in Perth Museum and the National Museum of Scotland. The Nicholsons of Kinclaven Farm very kindly allowed us to examine a beautifully preserved 1st century rotary quern found on their land and Prof E. McKie confirmed its identification. Maj Procter and Brig Ogilvie-Wedderburn of the Black Watch Museum helped us to identify Napoleonic milliaria found during fieldwalking at Cardean. Glamis Castle allowed access to their estate records for the site and the Angus Folk Museum helped us to identify other fieldwalking finds. Douglas Wares and Andy and Eleanor Graham have once again provided accommodation and, as always, we are more than grateful for the help of our many field volunteers and to the farmers and land owners who have allowed us access to sites, sometimes for weeks at a time.

Finally we thank Miss Ruth Dundas for her help during the Inverquharity survey and both SUAT and Geoscan for their lightening response when we suffered a broken resistivity meter probe. This could have led to several wasted days, but the former lent us a replacement meter frame on zero notice, whilst the latter had a replacement part rushed to Scotland by the next day. To our amazement, the local bus company depot also managed to weld the original part back together and the eventual time lost was less than an hour.

The Future

2003 should be another busy year for the Project, with a number of ventures in preparation. In the field the most important event will be the continued excavation at East Coldoch, with a slightly longer, three week season planned. We also intend to continue our series of whole Roman fort geophysical surveys. We still have our eye on Bochastle fort and temporary camps, but our growing interest in Roman/native interaction is starting to make the fort of Cargill a higher priority target. This is actually a double site, with an Inverquharity sized, 1 acre fortlet and a full sized auxiliary fort in adjoining fields, both of which have native structures around them. The two sites are on separate farms and so require separate land owner consents. Permission has already been obtained for the fortlet and an approach has been made for the fort. Our air photographic program will continue and, as mentioned, we plan to conduct shadow light flying during this winter as well as hoping for a better crop mark season in the summer.

On the publication side, the Cardean report is scheduled to be completed by spring and reports on Raith and Inverquharity should be ready by the same time. Our excavations at Garnhall Roman tower should be ready for print later in the year and Dr Hoffmann’s book on the glass of Newstead fort, with its review of glass finds throughout Roman Scotland, should also be completed during the year. Since the East Coldoch excavation is to continue, a final report may not appear for some years. We have, therefore, decided to prepare a detailed interim report to allow wider access to the results to date and this is now nearing completion. In all probability it will be a web, rather than paper publication, but the final decision has not yet been taken. The Directors will both be presenting papers to the Congress of Roman Frontier Studies (and its proceedings volume) and the Web site will continue to be kept up to date. Finally, public lectures by the both Directors have already been booked and others will no doubt be scheduled as the year progresses.